Abstract

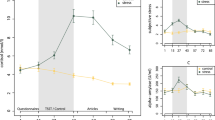

Many important decisions are made under stress and they often involve risky alternatives. There has been ample evidence that stress influences decision making, but still very little is known about whether individual attitudes to risk change with exposure to acute stress. To directly evaluate the causal effect of psychosocial stress on risk attitudes, we adopt an experimental approach in which we randomly expose participants to a stressor in the form of a standard laboratory stress-induction procedure: the Trier Social Stress Test for Groups. Risk preferences are elicited using a multiple price list format that has been previously shown to predict risk-oriented behavior out of the laboratory. Using three different measures (salivary cortisol levels, heart rate and multidimensional mood questionnaire scores), we show that stress was successfully induced on the treatment group. Our main result is that for men, the exposure to a stressor (intention-to-treat effect, ITT) and the exogenously induced psychosocial stress (the average treatment effect on the treated, ATT) significantly increase risk aversion when controlling for their personal characteristics. The estimated treatment difference in certainty equivalents is equivalent to 69 % (ITT) and 89 % (ATT) of the gender-difference in the control group. The effect on women goes in the same direction, but is weaker and insignificant.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For example, if the participant preferred the lottery up to row 6 (safe amount = 1500 ECU) and switched to preferring the safe amount starting in row 7 (safe amount = 1800 ECU), 1650 ECU is taken as the certainty equivalent. For the interval regression, the certainty equivalent is defined as lying between 1500 and 1800 ECU.

The detailed treatment and control instructions and protocol scripts are provided in the Electronic supplementary material.

Saliva samples were collected using a standard sampling device Salivette. The samples were frozen to \(-\)20 \(^{\circ }\)C after each experimental session and the salivary cortisol concentration was analyzed by the laboratory of the Biopsychology department at TU Dresden and by the Department of the Clinical Biochemistry at the Military Hospital in Prague. Prior to the experiment we conducted a separate pilot session where only the TSST-G procedure was administered and five saliva samples were collected and analyzed. The dynamics of the cortisol elevation in the pilot session followed the trajectory common in the literature (e.g. in von Dawans et al. 2011) including the recovery phase and therefore we assume the same trajectory in our subjects. Moreover, cortisol levels show a short-term pulsatility and therefore only one post-stress sample is insufficient to prove the increase in cortisol levels (Young et al. 2004).

The types used are Polar RS400 and Polar S725X which are composed of a wireless chest transmitter and a wrist monitor. The recording precision was 1 s (Polar RS400) or 5 s (Polar S725X).

An English version of the MDMQ was used. Available at:http://www.metheval.uni-jena.de/mdbf.php.

For session 1 only 11 participants arrived.

See Online Appendix for details about the design of the Bayesian updating task. This task does not confound the results in this paper as subjects learned about their payment from the Bayesian updating task only at the end of the experiment. Even though subjects’ expected earnings may still matter, we do not consider this as issue as the TSST-G treatment group actually earned slightly more money in the Bayesian task compared to the control group, but the difference is not significant.

Above-normal weight (BMI above 25) and the intake of hormonal contraceptives may affect cortisol response to stress (Kudielka et al. 2009). Out of the 26 women indicating intake of oral contraceptives, 13 were assigned to the treatment group.

One subject left in the pilot session prior to the TSST-G procedure, confirming that this option was salient enough.

The maximum cortisol response is not available for two subjects in the control group, where saliva samples could not be analyzed.

We perform two robustness checks of our results, in which we do not drop the multiple switchers from the analysis. In the first robustness check, risk preferences are measured not using the elicited certainty equivalent, but using the number of risky choices made. We then estimate the ITT of stress on risk preferences using ordered probit. As a second robustness check, we treat the inconsistent subjects as indifferent between the safe amounts and the lottery for the entire interval in which multiple switches occur, as suggested by Andersen et al. (2006). This means that the certainty equivalent of these subjects is elicited in a wider interval than the certainty equivalent of subjects who switch just once. The ITT of stress on risk preferences is then estimated using interval regression. The results of both robustness checks are reported in Table 5 in the Online Appendix and show that results presented in the main text are robust to including the multiple switchers.

Similarly as in the case of ITT analysis, in Online Appendix Table 10 we run a sensitivity analysis to check which of the additional controls influence the results in the gender-specific regressions of Table 2. The results point to the same conclusion as in the case of ITT analysis.

This was calculated using the cmp module in Stata (Roodman 2015).

In Online Appendix Table 11, we again run a sensitivity analysis to check which of the additional controls influence the results in the gender-specific regressions of Table 3. As in the case of ITT analysis, the results are very similar if we control for neuroticism only.

To support this argument, consider that under stress, there are many other hormones released: First, the autonomic nervous system activates the adrenal medulla to release adrenaline and nor-adrenaline. Second, the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis follows with the secretion of vasopressin and corticotropin-releasing hormones in the hypothalamus. These hormones in turn stimulate the secretion of adrenocorticotropic hormone in the pituitary, which then triggers the massive secretion of cortisol in the adrenal glands (Kemeny 2003). We take cortisol as a proxy of the physiological response mainly due to the convenience of its measurement, but we do not claim that it is only cortisol which causes the effects on behavior.

See Buckert et al. (2014) for a detailed comparison of psychological studies on this topic.

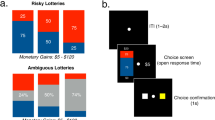

The risk-preferences tasks that have been used in previous studies such as the Balloon Analogue Task (Lejuez et al. 2002), the Game of Dice Task (Starcke et al. 2008) and the Iowa Gambling Task (Bechara et al. 1994) all include feedback processing, which is a potential confound. Other standard measures like Holt and Laury (2002) and Becker et al. (1964) may be too complicated to understand, which may be amplified under stress and thus again confound the results.

References

Allen, A. P., Kennedy, P. J., Cryan, J. F., Dinan, T. G., & Clarke, G. (2014). Biological and psychological markers of stress in humans: Focus on the trier social stress test. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 38, 94–124.

Andersen, S., Harrison, G. W., Lau, M. I., & Rutström, E. E. (2006). Elicitation using multiple price list formats. Experimental Economics, 9(4), 383–405.

Anderson, L. R., & Holt, C. A. (1997). Information cascades in the laboratory. The American Economic Review, 87(5), 847–862.

Ariely, D., Gneezy, U., Loewenstein, G., & Mazar, N. (2009). Large stakes and big mistakes. Review of Economic Studies, 76(2), 451–469.

Baum, A., & Grunberg, N. E. (1997). Measuring stress hormones. In S. Cohen, R. C. Kessler, & L. U. Gordon (Eds.), Measuring stress: A guide for health and social scientists, chapter 8 (pp. 175–192). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Baur, D. G., & McDermott, T. K. (2010). Is gold a safe haven? International evidence. Journal of Banking & Finance, 34(8), 1886–1898.

Bechara, A., Damasio, A. R., Damasio, H., & Anderson, S. W. (1994). Insensitivity to future consequences following damage to human prefrontal cortex. Cognition, 50, 7–15.

Becker, A., Deckers, T., Dohmen, T., Falk, A., & Kosse, F. (2012). The Relationship Between Economic Preferences and Psychological Personality Measures. Annual Review of Economics, 4(1), 453–478.

Becker, G. M., DeGroot, M., & Marschak, J. (1964). Measuring utility by a single response sequential method. Behavioral science, 9(3), 226–232.

Borghans, L., Duckworth, A., Heckman, J., & ter Weel, B. (2008). The economics and psychology of personality traits. Journal of Human Resources, 43(4), 972–1059.

Buckert, M., Schwieren, C., Kudielka, B. M., & Fiebach, C. J. (2014). Acute stress affects risk taking but not ambiguity aversion. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 8(May), 82.

Callen, M., Isaqzadeh, M., Long, J. D., & Sprenger, C. (2014). Violence and risk preference: Experimental evidence. The American Economic Review, 104(1), 123–148.

Cameron, L., Erkal, N., Gangadharan, L., & Zhang, M. (2015). Cultural integration: Experimental evidence of convergence in immigrants preferences. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 111, 38–58.

Capra, C. M., Jiang, B., Engelmann, J. B., & Berns, G. S. (2013). Can personality type explain heterogeneity in probability distortions? Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 6(3), 151–166.

Cassar, A., Healy, A., & Von Kessler, C. (2011). Trust, risk, and time preferences after a natural disaster: Experimental evidence from Thailand. New York: Mimeo.

Charness, G., & Gneezy, U. (2012). Strong evidence for gender differences in risk taking. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 83(1), 50–58.

Chemin, M., Laat, J. D., & Haushofer, J. (2013). Negative rainfall shocks increase levels of the stress hormone cortisol among poor farmers in kenya. New York: Mimeo.

Clow, A. (2001). The physiology of stress. In F. Jones & J. Bright (Eds.), Stress, myth, theory, and research (pp. 47–61). Harlow: Pearson Education.

Coates, J. M., & Herbert, J. (2008). Endogenous steroids and financial risk taking on a London trading floor. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(16), 6167–72.

Cohn, A., Engelmann, J., & Fehr, E. (2015). Evidence for countercyclical risk aversion : An experiment with financial professionals. The American Economic Review, 105(2), 860–885.

Cornelisse, S., van Ast, V. A., Haushofer, J., Seinstra, M. S., Kindt, M., & Joëls, M. (2013). Time-dependent effect of hydrocortisone administration on intertemporal choice. New York: Mimeo.

Costa, J. P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO personality inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4(1), 5–13.

Croson, R., & Gneezy, U. (2009). Gender differences in preferences. Journal of Economic Literature, 47(2), 448–474.

Deck, C., Lee, J., Reyes, J. (2010). Personality and the consistency of risk taking behavior: Experimental evidence. Chapman Univesity Working Paper, (10–17).

Deck, C., Lee, J., Reyes, J., & Rosen, C. (2012). Risk-taking behavior: An experimental analysis of individuals and Dyads. Southern Economic Journal, 79(2), 277–299.

Dedovic, K., Rexroth, M., Wolff, E., Duchesne, A., Scherling, C., Beaudry, T., et al. (2009). Neural correlates of processing stressful information: An event-related fMRI study. Brain research, 1293, 49–60.

Dickerson, S. S., & Kemeny, M. E. (2004). Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin, 130(3), 355–391.

Dohmen, T. (2008). Do professionals choke under pressure? Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 65(3–4), 636–653.

Dohmen, T., & Falk, A. (2011). Performance pay and multidimensional sorting: Productivity, preferences, and gender. The American Economic Review, 101(2), 556–590.

Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., & Sunde, U. (2010). Are risk aversion and impatience related to cognitive ability? The American Economic Review, 100(3), 1238–1260.

Eckel, C. C., El-Gamal, M. A., & Wilson, R. K. (2009). Risk loving after the storm: A Bayesian-Network study of Hurricane Katrina evacuees. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 69(2), 110–124.

Fischbacher, U. (2007). Z-TREE: Zurich toolbox for ready-made economic experiments. Experimental Economics, 10(2), 171–178.

Foley, P., & Kirschbaum, C. (2010). Human hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis responses to acute psychosocial stress in laboratory settings. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 35(1), 91–96.

Goldberg, L. R., Johnson, J. A., Eber, H. W., Hogan, R., Ashton, M. C., Cloninger, C. R., & Gough, H. G. (2006). The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(1), 84–96. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.007.

Goldstein, D. S., & McEwen, B. S. (2002). Allostasis, homeostats, and the nature of stress. Stress, 5(1), 55–58.

Greiner, B. (2004). An online recruitment system for economic experiments. In K. Kremer & V. Macho (Eds.), Forschung und wissenschaftliches Rechnen GWDG Bericht. Göttingen: Gesellschaft fur Wissenschaftliche Datenverarbeitung.

Guiso, L., & Paiella, M. (2008). Risk aversion, wealth, and background risk. Journal of the European Economic Association, 6(6), 1109–1150.

Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., Zingales, L. (2013). Time varying risk aversion. NBER Working Paper #19284.

Haushofer, J., Cornelisse, S., Seinstra, M., Fehr, E., Joëls, M., & Kalenscher, T. (2013). No effects of psychosocial stress on intertemporal choice. PLoS One, 8(11), e78597.

Haushofer, J., & Fehr, E. (2014). On the psychology of poverty. Science, 344(6186), 862–867.

Haushofer, J., & Shapiro, J. (2013). Household response to income changes : Evidence from an unconditional cash transfer program in Kenya. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Heckman, J. (2011). Integrating personality psychology into economics. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper Series, No. 17378.

Holt, C. A., & Laury, S. K. (2002). Risk aversion and incentive effects. The American Economic Review, 92(5), 1644–1655.

Kajantie, E., & Phillips, D. I. W. (2006). The effects of sex and hormonal status on the physiological response to acute psychosocial stress. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 31(2), 151–178.

Kandasamy, N., Hardy, B., Page, L., Schaffner, M., Graggaber, J., Powlson, A. S., et al. (2014). Cortisol shifts financial risk preferences. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 111(9), 3608–13.

Kaul, A., & Sapp, S. (2006). Y2K fears and safe haven trading of the U.S. dollar. Journal of International Money and Finance, 25(5), 760–779.

Kemeny, M. E. (2003). The psychobiology of stress. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(4), 124–129.

Kirschbaum, C., Kudielka, B. M., Gaab, J., Schommer, N. C., & Hellhammer, D. H. (1999). Impact of gender, menstrual cycle phase, and oral contraceptives on the activity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 61(2), 154–62.

Kirschbaum, C., Pirke, K. M., & Hellhammer, D. H. (1993). The “Trier Social Stress Test”—A tool for investigating psychobiological stress responses in a laboratory setting. Neuropsychobiology, 28(1–2), 76–81.

Kudielka, B. M., Hellhammer, D. H., & Wüst, S. (2009). Why do we respond so differently? Reviewing determinants of human salivary cortisol responses to challenge. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(1), 2–18.

Lejuez, C. W., Read, J. P., Kahler, C. W., Richards, J. B., Ramsey, S. E., Stuart, G. L., et al. (2002). Evaluation of a behavioral measure of risk taking: The Balloon Analogue Risk Task (BART). Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 8(2), 75–84.

Lighthall, N. R., Mather, M., & Gorlick, M. A. (2009). Acute stress increases sex differences in risk seeking in the balloon analogue risk task. PLoS One, 4(7), e6002.

Malmendier, U., & Nagel, S. (2011). Depression babies: Do macroeconomic experiences affect risk taking? The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(1), 373–416.

Michl, T., Koellinger, P., Picot, A. O. (2011). In the mood for risk? An experiment on moods and risk preferences. Ludwig-Maximilians University Working Paper Series.

Miller, R., Plessow, F., Kirschbaum, C., & Stalder, T. (2013). Classification criteria for distinguishing cortisol responders from nonresponders to psychosocial stress: evaluation of salivary cortisol pulse detection in panel designs. Psychosomatic Medicine, 75(10), 832–840.

Nguyen, Y., & Noussair, C. (2014). Risk aversion and emotions. Pacific Economic Review, 19(3), 296–312.

Oberlechner, T., & Nimgade, A. (2005). Work stress and performance among financial traders. Stress and Health, 21(5), 285–293.

Pabst, S., Brand, M., & Wolf, O. T. (2013a). Stress and decision making: A few minutes make all the difference. Behavioural Brain Research, 250, 39–45.

Pabst, S., Brand, M., & Wolf, O. T. (2013b). Stress effects on framed decisions: there are differences for gains and losses. Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 7, 142.

Petzold, A., Plessow, F., Goschke, T., & Kirschbaum, C. (2010). Stress reduces use of negative feedback in a feedback-based learning task. Behavioral Neuroscience, 124(2), 248–255.

Porcelli, A. J., & Delgado, M. R. (2009). Acute stress modulates risk taking in financial decision making. Psychological Science, 20(3), 278–283.

Roodman, D. (2015). CMP: Stata module to implement conditional (recursive) mixed process estimator. Statistical software components. https://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s456882.html

Schipper, B. (2012). Sex hormones and choice under risk, No. 12, 7. Working Papers, Department of Economics, University of California. http://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/58361

Starcke, K., & Brand, M. (2012). Decision making under stress: A selective review. Neuroscience and biobehavioral reviews, 36(4), 1228–1248.

Starcke, K., Wolf, O. T., Markowitsch, H. J., & Brand, M. (2008). Anticipatory stress influences decision making under explicit risk conditions. Behavioral Neuroscience, 122(6), 1352–1360.

Steyer, R., Schwenkmezger, P., Notz, P., & Eid, M. (1997). MDBF-Mehrdimensionaler Befindlichkeitsfragebogen. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Taylor, S. E., Klein, L. C., Lewis, B. P., Gruenewald, T. L., Gurung, R. A. R., & Updegraff, J. A. (2000). Biobehavioral responses to stress in females: Tend-and-befriend, not fight-or-flight. Psychological Review, 107(3), 411.

United Nations. (2015). The millennium development goals report. Technical Report, United Nations, New York

Upper, C. (2000). How Safe Was the“Safe Haven” ? Financial Market Liquidity during the 1998 Turbulences. Discussion paper, Economic Research Group of the Deutsche Bundesbank, 1(February).

van den Bos, R., Harteveld, M., & Stoop, H. (2009). Stress and decision-making in humans: Performance is related to cortisol reactivity, albeit differently in men and women. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 34(10), 1449–1458.

Vieider, F. M., Lefebvre, M., Bouchouicha, R., Chmura, T., Hakimov, R., Krawczyk, M., et al. (2014). Common components of risk and uncertainty attitudes across contexts and domains: Evidence from 30 countries. Journal of the European Economic Association, 13, 1–32.

von Dawans, B., Fischbacher, U., Kirschbaum, C., Fehr, E., & Heinrichs, M. (2012). The social dimension of stress reactivity: Acute stress increases prosocial behavior in humans. Psychological Science, 23(6), 651–660.

von Dawans, B., Kirschbaum, C., & Heinrichs, M. (2011). The trier social stress test for groups (TSST-G): A new research tool for controlled simultaneous social stress exposure in a group format. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 36(4), 514–522.

Voors, M. J., Nillesen, E. E. M., Verwimp, P., Bulte, E. H., Lensink, R., & Soest, D. P. V. (2012). Violent conflict and behavior: A field experiment in Burundi. The American Economic Review, 102(2), 941–964.

Yesuf, M., & Bluffstone, R. A. (2009). Poverty, risk aversion, and path dependence in low-income countries: Experimental evidence from Ethiopia. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 91(4), 1022–1037.

Young, E. A., Abelson, J., & Lightman, S. L. (2004). Cortisol pulsatility and its role in stress regulation and health. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 25, 69–76.

Acknowledgments

We want to express special gratitude to Michal Bauer for his help and encouragement. Next we express our thanks to Mathias Wibral, Frances Chen, Bertil Tungodden, Peter Martinsson, the editor and referees of this journal and the audience at 2013 Florence Workshop on Behavioral and Experimental Economics for their valuable comments; Bernadette von Dawans and Clemens Kirchbaum for providing all materials and helpful advice for the execution of the TSST-G procedure. The possibility to use the Laboratory of Experimental Economics in Prague and the possibility to use the heart-rate monitors of Faculty of Physical Education and Sport, Charles University are also gratefully acknowledged. We also thank Miroslav Zajicek, Klara Kaliskova, Lukas Recka, Tomas Miklanek, Jan Palguta, Michala Tycova, Ian Levely, Dagmar Strakova, Vaclav Korbel, Jane Simpson and Zuzana Cahlikova for their help with data collection. All errors remaining in this text are the responsibility of the authors. The research was supported by GA UK grant No. 4046/11. Jana Cahlíková also acknowledges support from the grant SVV-2012-265 801 and Lubomír Cingl acknowledges support by the grant SVV-2012-265 504.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Cahlíková, J., Cingl, L. Risk preferences under acute stress. Exp Econ 20, 209–236 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-016-9482-3

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10683-016-9482-3